🎮 Humankind and the rhetoric of tech trees

(Part of a series on games and models)

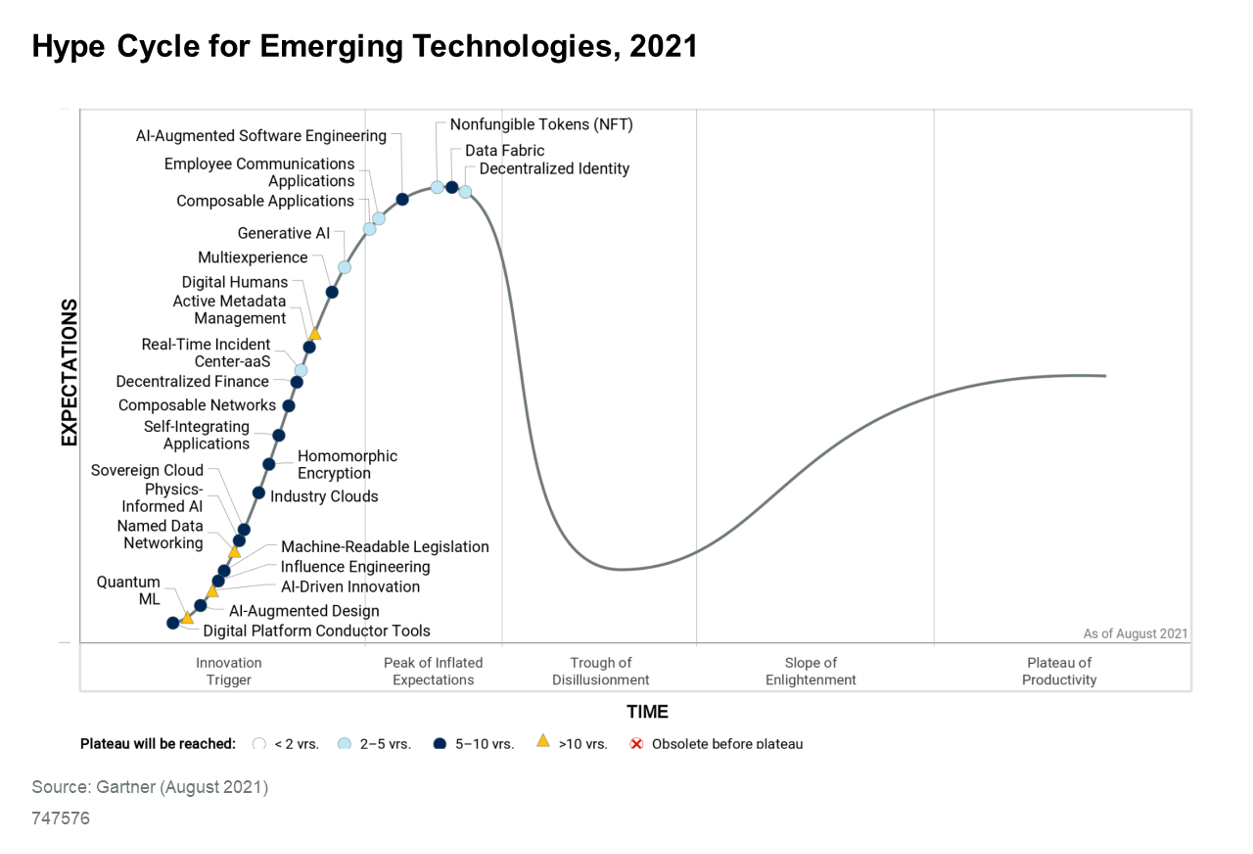

If you're at all interested in technology, you've probably come across the “Gartner hype cycle” model of technology development. Here's an example from last year:

The hype cycle argues that innovation matures in stages, but the result is a bit like the Hero's Journey of the tech world — it's well known, narratively compelling, but… as a model of the real world, it misses many things, and its assumptions simply don't bear out.

For example: the model suggests that the cycle is the same for every technology, or that the stages are fixed and that criticism is followed by eventual adoption. But these ideas don't stand up to historical review. In fact, real technologies mostly don't follow such a cycle at all.1

But the hype cycle, as a model, also tells a narrative.

It's a narrative of progress in the face of adversity. The path goes from rejection towards eventual adoption, and there is no off-ramp from the cycle — failure is not modeled. People looking to this model for guidance might understandably forget the myriad ways in which technologies fail all the time.

It's therefore useful as a rhetorical device that argues for a point of view. For example, a startup that needs to buy time from investors or the press, can use this framework to argue that every great idea goes through a rejection phase on the way to mass adoption. All they need is a little bit more money and patience, and they'll surely get there.

Because in this model, that is the only path.

In games we have our own version of a predestined technology model.

The venerable tech tree is a way to describe how the player's technology will grow over time. Tech trees are as old as PC games, and we've all seen them in countless titles: for example, as a series of technologies that unlock upgrades or units.

Tech trees are a solution to a very mundane problem: how to give the player a feeling of progression, of getting better, of learning new things and discovering new abilities.

There are many ways to do this (e.g. progression mechanics, levels, XP), but the tech tree has some nice advantages: unlike abstract progression mechanics, tech trees make it easy to fictionalize progress (e.g. you “just discovered nuclear power! electricity costs are reduced”) — and also, since it's a graph, it's easy to visualize how technologies depend on each other (e.g. you can't discover nuclear power unless you've discovered physics first).

But for games that are situated in the real human world, tech trees end up also commenting on human advancement, and that's where things get interesting.

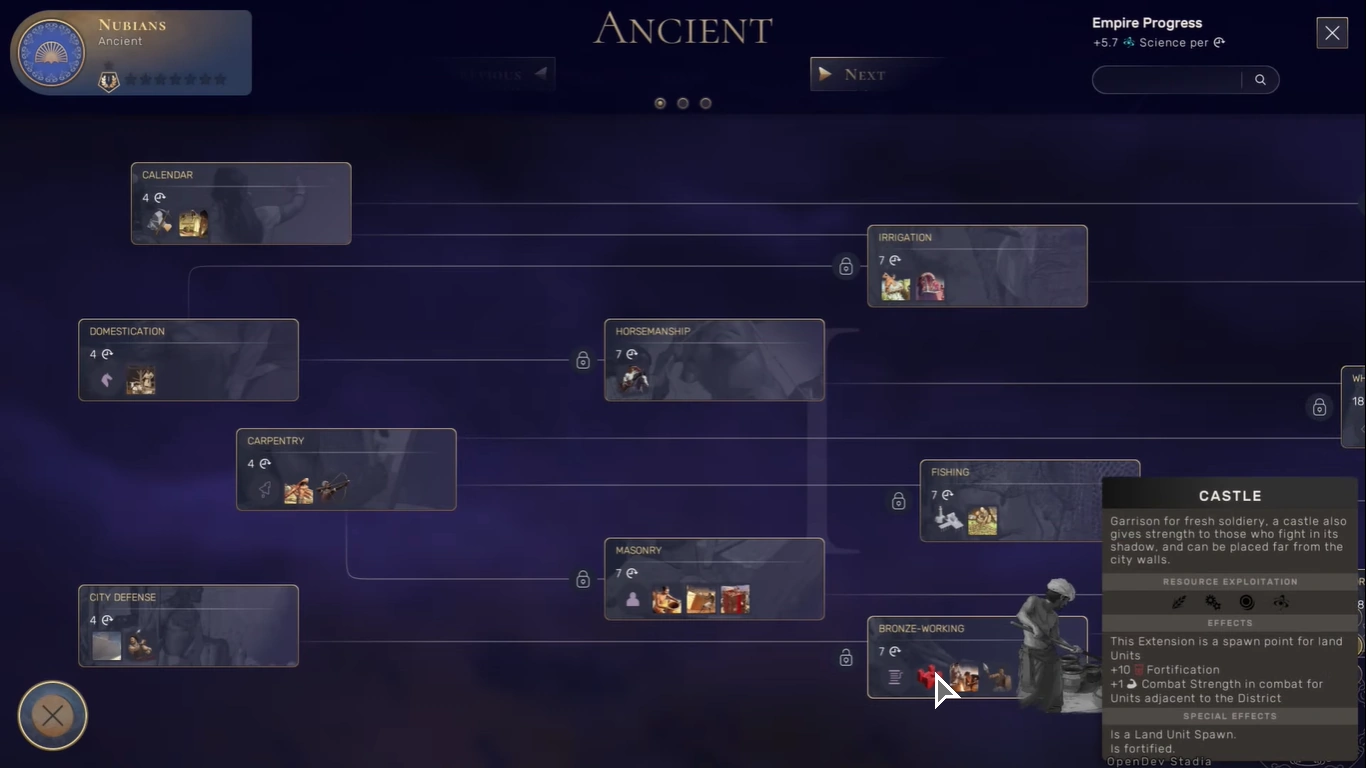

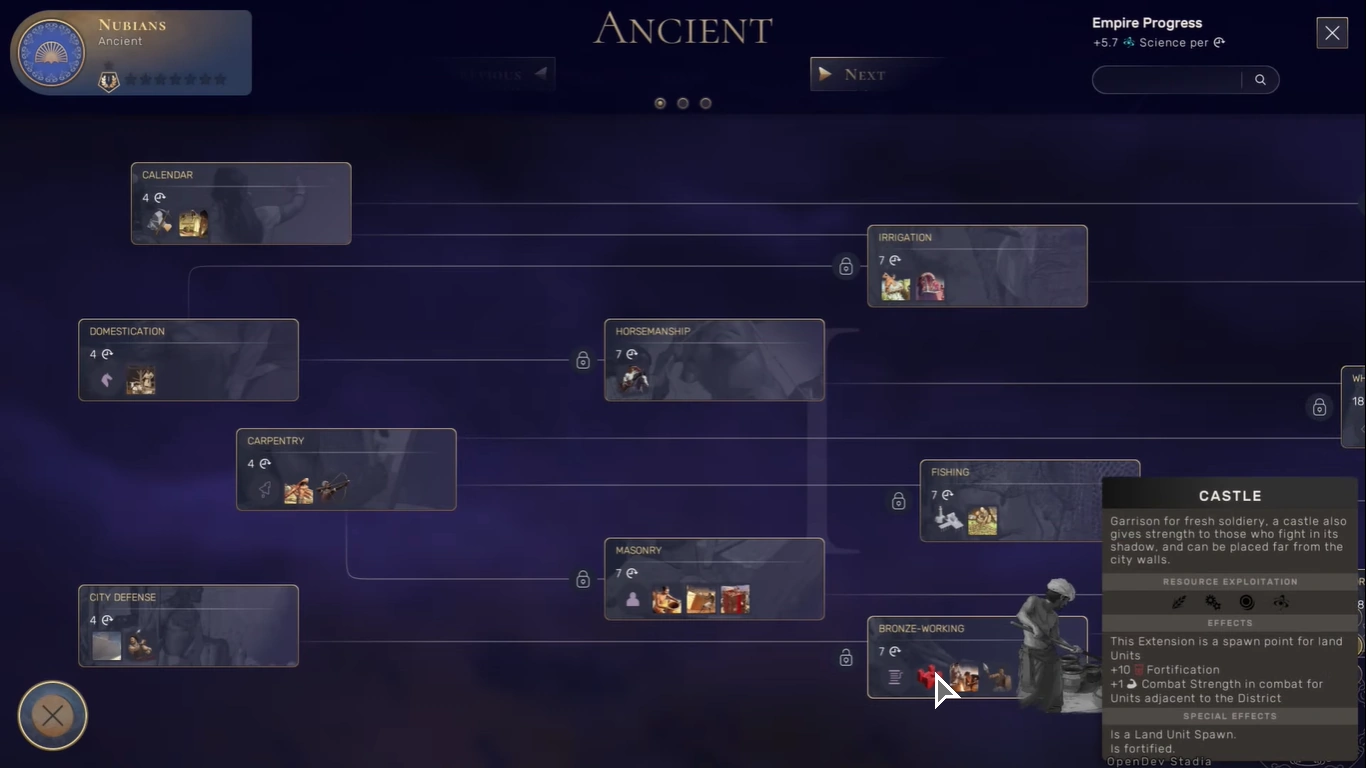

For example, here are two screenshots showing a fragment of the tech tree in the game Humankind:

Since Humankind is a strategy game with a broad historical sweep, the tech tree similarly follows the contours of human technical achievements. In the “Ancient Era”, the player can develop 12 techs like irrigation, writing, or organized warfare. As we go through the ages, this continues: the “Classical Era” allows for 12 more including philosophy and rhetoric, as well as standing army or siege tactics; similarly with other eras from medieval to modern. At each point, new technologies unlock new buildings, improvements, armies — and other future technologies.

But a tech tree that describes human progress through history can't help but embody some specific historical perspectives. Simply put, the choice of which technologies to include, and which not to include, is a perspective on what's important to humankind (and to Humankind).

For example, the game's tech tree includes 93 technologies of various types, from irrigation to the fusion reactor. But of those 93, fully 31 techs are military innovations dedicated to warfare (e.g. heavy infantry, or siege cannons), while most other non-military ones unlock secondary military capabilities (e.g. bronze working unlocking spearmen).

And also, consider what's excluded. In Humankind, a number of human innovations simply don't exist. Poetry as such never appears in antiquity, and neither does theater, religion, or mathematics. Renaissance never sees architecture or astronomy; industrial age has no chemistry or physics.

Instead the tech tree offers other options: organized warfare, standing armies, conquest, siege tactics, military architecture. And in industrial times, guerilla warfare and military coordination claim equal importance to electricity and the scientific method.

In this tech tree, the arts and sciences are simply not a part of the model. They don't exist in the game world, they can't be researched, they're not part of human history at all. Instead, war technologies are first-class innovations, and must be researched in order to progress through history.

This is a very martial view of history, of what kinds of human developments are worthy of rememberance.

But this isn't the only way this could have played out. For instance, if we look at another game like Civilization 5 (which was a clear inspiration behind Humankind), its tech tree is very different. All the items I mentioned as missing, the various arts and sciences, show up there.

In Civilization 5, the human civilization discovers poetry and drama and mathematics and architecture; the history of humanity is filled to the brim with accomplishments of the human spirit. And out of the 83 techs, only 8 are dedicated to war; instead, military upgrades come as side-effects of other innovations.

In short, Civilization seems to be more interested in civilization construed broadly, rather than focusing on its military passions.2

This rhetorical shape of the tech tree changes the tenor of the game.

And I don't know whether this particular rhetorical shape was intentional. The tech tree is a utilitarian beast, meant to guide the player through the game's systems — and if the game is primarily a military strategy game, oriented around territory and offense and defense, it seems natural that the tech tree would match that, to guide and reward the player accordingly.

But consider the player fantasy that comes out of that.

As a player, you're no longer playing a game where your civilization discovers poetry and religion and democracy. Instead you're playing a civilization that discovers mounted warfare and naval artillery and trench warfare. And once you start playing a game, you have no choice, you have to submit to the model it presents.

In the end, the two games, Humankind and Civilization 5 present starkly different visions of humanity's history — one focused on warfare and conquest, and the other celebrating the joyful and innovative human spirit. They tell very different stories of humankind.

And what's amazing, is that they tell these stories entirely through game systems.

-

Re hype cycle, here's a fun-yet-charitable analysis: LinkedIn - and a more theoretical and detailed one: ResearchGate.↩

-

But this is not an invariant across all Civilization games. Older games like Civ 4 included ideas like democracy in the tech tree, which later games represent as orthogonal civic innovations. And by the time we get to Civ 6, things change towards the martial again - out of the 77 techs in Civ 6, 12 are military; poetry and drama and theology are out; military engineering and siege tactics are in.↩